Overcoming Passivity in Your Jiu Jitsu

7 tips for increasing your competitive spirit and intensity

The biggest thing I’ve been working on the past 3 months has been increasing my level of aggressiveness and tempo in jiu jitsu. I was being too passive for a number of psychological reasons that I won’t get into, but I was also getting mad at myself for being unable to overcome the passivity.

It’s taken a lot of work, but I finally feel like I can turn “on” my aggression and fighting spirit, instead of giving up because I’m too tired or scared or whatever reason I come up to justify anything less than my full effort. One unexpected benefit of this change is that I felt considerably less anxious and more prepared for my school’s recent in-house tournament. I didn’t have a question of whether or not I could “go hard” and fight out of bad positions because I had specifically trained for those scenarios.

I want to emphasize that I’ve tried many times to find this turbo-charged version of myself during sparring, to varying degrees of success. I think the approach cannot be a one-size-fits-all method, though I feel like I did do some things differently which helped me get further this time around. So, I’m sharing these options (and mistakes) here in the hopes that people can use them as a starting point in their own journey.

Option #1: Choose the moments in which you decide to go “all out”

When I first started thinking about “becoming more aggressive,” I started to feel a lot of anxiety before and during classes. In my mind, if I had to focus on “going 100%” then it meant that I had to look, feel, and be hardcore for all rounds in every single class. I felt like if I had to flip a switch, it had to stay on for any meaningful change to happen.

Meaningful change did happen, but it wasn’t necessarily positive. The unnecessary pressure I put on myself to “do my best” all the time was draining, not only physically, but mentally as well. When I confided to a mentor about feeling burned out, they suggested that I only work on going “all out” in smaller moments — 1 or 3 minute rounds, only a handful of times a week. Or, if that was too much for me to handle, then to go “all out” on ONE sweep or submission attempt.

As it turned out, my brain is really good at making sure that I always preserve a little bit of myself for survival reasons. This meant that if I told myself that I would try to fight to the death for 6 rounds, my brain wouldn’t let me or it would make damn well sure that I didn’t feel good for trying (eg pumping out anxious thoughts).

But, I could override that survival impulse if I knew it was only for an absurdly short period of time. Like most of my skill acquisition has shown me so far, the results were bound to be better and longer lasting if I narrowed the scope of changes and built from the ground up.

Option #2: Set yourself up for success with micro-adjustments before training

One thing that I’ve learned from my meditation practice is that meditation is no different than how one may behave outside of the formal practice. For instance, the attitude of present awareness can apply whether someone is sitting at their work desk or meditation spot. There is no artificial separation because you are still living with the same mind.

It seems obvious, but when I come to jiu jitsu feeling stressed out, hungry, tired, or a combination thereof, it’s a lot harder for me to perform better and to push myself. Conversely, I also know how much harder it is to try to do all of the self-care activities day in and day out. Some of us don’t have jobs or lifestyles that allow us to always get optimal sleep and nutrition.

That’s why, over the course of tweaking my own habits and routines, I’ve started to focus more on micro-moments of preparation that give me the best benefits. Micro-prep means taking one thing and trying to do that a little better than the baseline. It takes some experimentation to know what works for you, but generally the list of options goes like this for me:

Keep a bottle of water at my desk at all time and be vigilant about taking a sip every time I think about using my phone or want to get distracted.

Spend 10 minutes in the evenings to pack my gear ahead of time.

Once a day, try to take 5 deep breaths to decompress.

Budgeting time to work on my jiu jitsu journal, or my personal feelings journal.

Putting my phone away and out of reach when I come back from jiu jitsu, so I’m less tempted to try to use my phone to decompress.

None of these things are particularly hard for me to do and they are all within my control. The cool thing is that when I focus on just one of them, I can have confidence that I am walking into the gym in just a little bit better shape than I would be otherwise.

Of course, if you would like to go all out of more ambitious goals, like getting adequate amounts of sleep on Mondays - Fridays, or hitting a daily protein goal, that’s totally awesome, too.

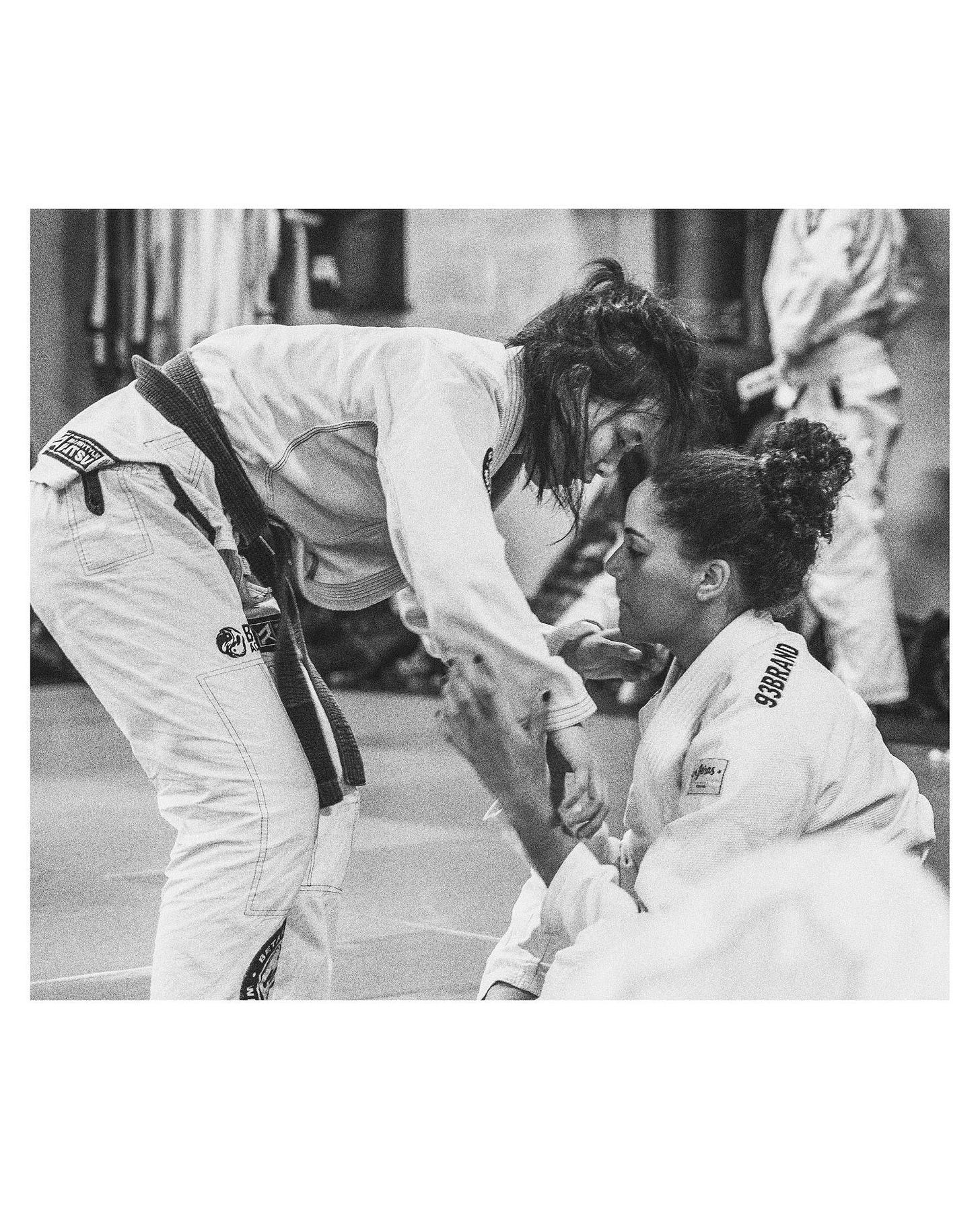

Option #3: Work with trusted partners who understand your intentions

When I first “decided” that I was going to go all out, I found a few people that I could try out my new version of sparring pace and intensity. The partner you find doesn’t necessarily need to be your size, but they must absolutely have the emotional maturity to stay in control of themselves. A good way to find these partners are usually those who are the best at flow rolling, because they have a good sense of how to move through as many positions as possible.

When you work with these partners, consider letting them know that you are trying to work on increasing your speed and intensity. Then — and this is a crucial step — tell them how they should react and what specific positions they should start in. This will allow you to get a chance to experience different types of resistance and gather data on what you respond well to or not.

For instance, when I was working on pin escapes, I felt very timid at first to use all of the tools available to me in order to recover my guard. Sometimes it was because I felt tired. Othertimes it was because I felt “mean” for putting my forearm in someone’s throat, even if it was to prevent them from putting their cross-face against my throat. Still other times, I felt awkward spazzing out without any real effect.

So I would find partners to help address each of these issues, with explicit instructions to let me work without fearing that they would spaz out or hurt me in the process. This might seem like overkill, but I consider it communication instead. Of course, in a real match, you don’t need permission to do the moves you need to do. You don’t need to concede positions. However, I do think working yourself up to that mindset of “I don’t need permission” does take some effort if you’re starting from a place of lower intensity. And also, it’s just common courtesy for your training partners to know what’s coming, even if it’s just a round where they’re being asked to lay there and prevent you from getting out of a pin.

Option #4: Increase your jiu jitsu knowledge on the “when” and “where” of a technique

I played piano and violin for many years in my youth, and part of playing music is in understanding the concept of rhythm and tempo for a piece.

Rhythm is how the notes in a piece relate to each other — are they far apart, close together, or a little bit of both?

Tempo is the underlying beat of a piece that is measured by beats per minute. When you turn on a metronome, you are tracking your tempo.

Something can have a consistent rhythm but no discernible tempo. For instance, a birdsong may follow a rhythm of sounds when the bird starts to chirp, but you may not know when the next series of sounds will begin.

Tempo is actually something that is up for interpretation, since tempo markings sometimes have different qualitative descriptions:

Largo – broadly (40–60 bpm)

Larghetto – rather broadly (60–66 bpm)

Adagio – slow and stately (literally, "at ease") (66–76 bpm)

And, where tempo is like a speed limit on a highway, there are often signs along the road that ask you to brake or speed up accordingly:

Rallentando – gradually slowing down

Ritardando – gradually slowing down (but not as much as rallentando)

Ritenuto – immediately slowing down

As a musician, you’re not just mechanically “hitting” notes, like a robot. You have to understand the nuances of the technique in order to interpret it and to make it your own.

Jiu jitsu is no different. Moves that have been done for years may possess a variety of rhythms. A single technique, when put in the context of other techniques, may also require a different rhythm to maximize the chances for success.

Part of the jiu jitsu practitioner’s task is to learn/figure out the tempo and rhythms that are appropriate for the situation at hand. I’m talking about knowing not just knowing that a “pressure” pass is slower than a “speed” pass, but finer points regarding tempo, like:

How long you can hold your initial grips before the opponent can counter effectively

How quickly you need to transition and advance to the next milestone in the pass (and what milestones are even there)

Moments in which you are vulnerable to counters/scrambles and the appropriate response (is it to shut them down, slow them down, or to speed yourself up?)

How the pass fits into your larger pace of offense (e.g., pass and immediately go to a submission, or pass and cook them under pressure)

Tip #5: Watch competition footage (especially no gi)

Your brain has a hard time distinguishing from reality and imagination. You can use this to your advantage by watching competition footage. I like to watch my favorite athletes compete because I can also learn from them at the same time. However, you don’t need to watch only for technique. You can watch to see how their intensity changes based on the situation, like whether they are losing/winning, whether they are in a bad/dominant positon, whether they have time to score or in overtime defense.

Also, take time to watch non-pros, or pros who compete at non-black belt levels. This is because these fights are more likely to be explosive since black belts are good at cancelling things out, so the pace of action might be slow. I’ve found the matches that are most helpful to getting my brain in that “kill” mode are matches between two roughly evenly matched purple/brown belts in submission-only overtime. When you watch the ferocity in which people try to attack or defend from a fully locked armbar or choke, you can start to pick up on the intensity subconsciously, too.

Finally, if you can, go to a tournament and simply spectate on the action. When you’re in a crowded space with people screaming at other people going hard after another, try to bottle up that feeling and convert it into your own energy. Sometimes, experiencing the overall look and feel of competition can help you start to transform your own mode of operation.

Option #6: Read and listen to sports psychology content (or any performance-related realm, like the music/dance/gaming)

There is a ton of literature and audio content out there regarding competition, intensity and focus. If you haven’t done so, cast a wide net and start to listen to everything that’s out there. I give this advice mainly because I’m the kind of person who likes to take in a ton of information and then whittle it down to the passages that resonate with me the most. And, reading about other stuff helps you get a different perspective than the likely repetitive dialogue going on inside your brain.

One adjustment that I made early on was to consume sports psychology content for people in sports other than jiu jitsu. It helps to have a bit of distance and to draw your own conclusions from an adjacent realm. Focusing on different sports reduces the temptation to take everything as an instant blueprint for jiu jitsu.

Option #7: Do serious soul-searching

Often — though not always — there is some sort of mental barrier that is preventing you from reaching your desired state of intensity. For instance, due to my past experiences and the beliefs I formed around them, my natural reaction when confronted with aggression was to withdraw. I became used to using avoidant strategies when it came to uncomfortable situations. I felt like I needed to people-please and to make assumptions about what people expected of me.

All of these mental barriers contributed some way to my ability to bring a certain level of intensity to my jiu jitsu. I don’t think I did this soul-searching necessarily just to make my jiu jitsu better, but rather, I used my training to reveal to me what I was struggling with as a holistic evaluation of myself:

What did my sometimesly absurdly irrational fear about offending someone say about my desire to stand my ground when I receive pushback?

Is there a reason why I’m afraid to make mistakes?

What is the driver behind my deferential attitude when rolling with people that I perceive have an advantage over me?

Why do I feel shy when confronted with aggression?

Am I afraid of finding out what my limits are?

It’s important to not rush through this process. I think when I began to think about the more difficult parts of myself, it quickly became overwhelming. Even though I love to write, writing about these emotions (even in private!) was difficult for me, so I could only manage small moments at a time.

And look here: I don’t want people to think that this introspection is being pushed on them. We don’t need to go to therapy for jiu jitsu (though we may benefit). But I think that a clear and honest reflection of what’s going on internally may be the best lever you can pull to change your external reality.

There has been no clear, linear, or simple path towards learning how to access my aggression in jiu jitsu. It has been a journey that I realize now will take me to unfamiliar places — being positive, authentic, and aware — not to impress others, but to show myself that I’m capable of that raw power that I have always suspected was in me.