The Dark Side of Jiu Jitsu Influencer Culture

shedding light into our sport’s obsession

When I started jiu jitsu, I started in one of the most famous academies in New York. I had no idea of the celebrities that trained there, no idea that people had traveled literally hundreds of miles and given up other careers or degrees to train at this school, and no idea of the jiu jitsu social scene as it existed both on and offline.

I quickly learned.

Influencers are defined by, well, their influence, which is generally accepted as directly correlated to the number of followers that they have, though there is a lack of consensus on the matter. Online influencers broadcast and reach their audience without the need for in-person, live events.

Furthermore, online influencers work to carefully cultivate an image of themselves as partaking in a well curated lifestyle. Often, real life does not reflect this curated set of events, but to preserve a “brand," influencers are incentivized to always present the best image of themselves. Their popularity requires them to be untouchable and unique, but also somehow relatable in a way that makes people want to be like them.

Most often the influencers are black belts, although a growing number of influencers are anywhere from blue to brown. Purple belt seems to be the turning point in the development of many people’s influencer choices, as they find more opportunities to broadcast their image through sponsors, superfights, and seminars. This makes sense, as a modest amount of money and reputation points can go to those with a good following and respectable competition wins.

Jiu jitsu influencers are proud to advertise their age (especially if under 25) and their most prestigious competition wins, particularly if they are from Euros, Pans, or Worlds. If they go to a celebrity school, or even not, you best believe that their school’s bio is tagged on there too. If they take a hard-earned recovery day, chances are you'll definitely learn about it, especially if the picture is paired with an inspirational quote about never giving up hope about attaining the next jiu jitsu goal.

If they place on the podium, regardless of the position, there are inevitably captions about working harder and “fixing their mistakes” for next time. Or, a series of short, pithy statements that read only half better than the one-sentence tomes on LinkedIn. They talk about missing a lifting PR, feeling fatigued from their personal training session (but still going to train every day, anyways), and winning despite being horrendously injured — as if this is somehow a noble struggle that should serve as inspiration.

Sound the humblebrag horns. The influencer has arrived.

Influencers are usually associated with brands, and in jiu jitsu, it is no different. Influencers will tag a number of brands on their bios, like DISCOUNT CODES; personal trainers/nutritionists/PTs; school name and lineage; CBD/supplements; gear/accessory companies.

Their call-to-action link in their bios are either to their sponsor websites (for competitors that have not yet caught the casual entrepreneur itch), a linktree, or a link to a 1x1 online membership waitlist. If they have a degree, the major will be featured prominently (usually something practical sounding, like economics, business administration or engineering) never mind that most likely their time isn’t spent developing professionally in that area. (And yes, while most of us don’t work directly in our field of academic study, most of us also do not continually trumpet our majors long after they have ripened.)

Four Horsemen of the Apocalpyse, move aside. We’ve got Beaches, Boobs, Butts and Belts coming through.

The classic jiu jitsu influencer aesthetic can evoke two strong reactions. The first, a “fondlebrag” is when the audience posts an endless stream of love bomb-esque comments that seeminly praise the person, but really upon closer inspection are inane at every angle. The second, a “hatescroll” is when you find yourself scrolling through nearly their entire feed, not because you can’t stop, but because you are a masochist. Either way, both actions leave the audience with a putrid aftertaste.

A jiu jitsu influencer has as good of a right as any to post pictures featuring that holy quartet. But, I’ve seen better. Erin Herle at first glance would appear to be a classic influencer, but her dedication and time to running a nonprofit, as well has her authentic vulnerability and a wickedly funny sense of humor, makes her approachable. It is a refreshing lift from the vapid influencer approach.

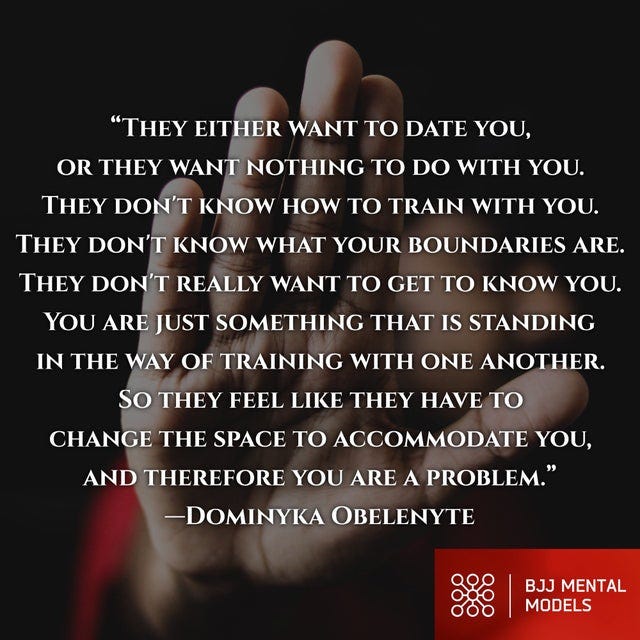

Another exception is Dominyka Obelenyte, who has used her competition fame not only for seminars and teaching, but also as a platform to express her views on how jiu jitsu can do and be better. Dominyka has prominently used her influence to speak out against the less savory aspects of jiu jitsu culture.

Emily Kwok is another individual who has used her jiu jitsu reputation to promote a number of creative projects and ideas. I’ve followed her blog on Princeton BJJ for a while and read her poignant Ode to Masters piece just as I was coming into masters age myself (That’s 30 for non-jitz people out there. I know. We age in dog years.)

Kwok’s piece on winning gold at Masters Worlds after a six year hiatus was hardly about herself — instead, it followed a lot of the principles that I appreciated when someone shares a success: making it about the people who helped them get there (instead of a lame excuse about how “no Instagram caption would do this moment justice”).

This fixation on a certain narrative makes the online landscape of jiu jitsu bland at best and toxic at worst. Here’s what one friend observed about jiu jitsu culture:

To have a lifestyle that allows you to collect pictures and moments of the different places you’ve traveled, the people you meet, and the lessons you learn is not inherently wrong. But at some point, the focus on monetizing these elements in the same tired narrative, to the near exclusion of anything else, is a disservice to jiu jitsu as a whole.

Are we human, or are we a group of acai-eating, protein-chugging, HIIT/CrossFit, sweaty mat surfing, basic hustleporn addicts that like to wear our injuries like badges of honor and never take any days off?

Jiu jitsu influencers, while they arguably get the most amount of attention and fuel for their ego, fail to take advantage of the opportunities before them to shape a more dynamic jiu jitsu culture and narrative. After a certain point of bastardized mimicry, the world of jiu jitsu deserves innovation in how it presents itself. Such innovation is crucial to marketing jiu jitsu to more people that may not consider jiu jitsu to be fitting for them at an initial glance, or simply being more accessible and less tone-deaf with regards to the hobbyists, who are the predominant crowd. Or perhaps, this is too much to ask for in a platform that rewards self-promotion.

I once had a friend who doubted if she could consider herself a martial artist because she did not “look” like the influencers that she saw on social media. I, too, doubted if I could call myself an athlete if I wasn’t working with a personal trainer, cutting weight, meeting personal records in the weightroom, collaborating with brands all while juggling a travel-heavy competition schedule and blasting highlight reels. After a while, I realized there was no true definition of an “athlete.” Maybe, just maybe, it would have been a more painless path had I had some better models.

More than anything, I hope that those who act like influencers are not actually extremely shallow, though I’m afraid I won’t be proven wrong. On a daily basis, they forcefeed the Scarcity Mindset while somehow advertising abundance in their own lives. The predominant message is “look at me, I’ve got something you don’t have, and that makes me better.”

Influencers are not born. Jiu jitsu influencers are made through a parthenogenetic process in the sterile, well-preened bubble of social media. Most people who start jiu jitsu don’t do it to become famous, or to make money. Somehow along the way, though, they get hooked on “being pro”—which is not terrible if done carefully. I believe that the transition should be intentional, not automatic, and certainly not a permanent path.

One might point out that with a little bit of emotional intelligence, us “normies” can recognize that influencers don’t actually influence the way that I, or anyone else, should see themselves. The same argument, though, can be made about influencers. What is their motivation to broadcast and perform every great moment to strangers? Is it because they might lack that emotional maturity themselves?

As I write in my essay “A Better Way to Get Better,” I believe that the optimal experience in jiu jitsu is one that lives entirely outside the sphere of being attached to external validation in your training. Hard to say that is possible when you broadcast the “best” moments of your life and wait for the likes to pour in.

Despite what influencers may argue, social media cannot be simply seen as just a “tool.” A tool has practical realities to it and hardly affects the nature of the person who uses it. Jiu jitsu and social media is instead, what it has always been—a game that may irrevocably harm both spectators and participants. Inevitably, the influencer culture sends the message to both practitioners and the outside world that this is what matters to us. This is what only matters to us.

I don’t know about you, but maybe I should compete on my birthday next time. Maybe, then, I’ll finally get this jiu jitsu thing.

Thank you for this. I never knew this world existed. As a martial artist of over 45 years experience in the UK I have to say I am appalled. I have seen stuff on Instagram and wondered what the heck it was all about (I thought it was just narcissists gone crazy), but now, reading this, I realise it is actually a 'thing'.

If you are interested look at my Substack area budojourneyman.substack.com , I am definitely following your posts!